This is what Arizona was supposed to look like. We were definitely in the desert now. Three foot (1 metre)-high fishhook cacti lined the trail, decorating yellow sandy grasslands as we hiked away from Reddington Road, the dirt track continuation of Tucson’s Tanque Verde (Green Tank) road, where a well-intentioned lady driver who had talked at us for the whole 45 minute ride had delivered us unceremoniously around midday.

Twists and turns and careful ankle slalom manoeuvres amongst the growing collection of cacti drew looming Rincon Mountains’ 8664 ft (2641 m) Mica Mountain peak and the prospect of a straight up, breathless 4257 ft (1297 m) climb quickly closer.

The uphill started before we knew it and the yellow grasses soon sprouted stunted flat-topped trees leaning away from the wind, straight out of South Africa. A big slab of stone which nestled between them and sheltered from the ominous mountain’s shadow became the lunch table and Glenn’s afternoon nap recliner.

That night, we camped near Tanque Verde Canyon at a tree-sheltered camp spot conveniently flattened out by others before us, where we inherited a stone camp ring offering a cosy backdrop to our ever-present salami sandwiches and our treats – sips of Scotch and nibbles of dark chocolate.

The next morning, after taking some close-ups of a dead but colourful grasshopper I’d nearly crushed on the trail the day before, carefully positioned to hide the leg which had broken off on his last trip clinging to my backpack, I found Glenn seated on a giant rounded stone throne just above the camp spot, reading the Economist with his back to the imposing mountain like a cat turns his back to his owner when he’s forgotten to feed him, with a stormy expression slapped on his face which said “why would I climb that massive mountain just so I can walk down the other side of it when there’s no one f****** chasing me?!?”

We’re much stronger now than we were at the start, but our brains haven’t reset their expectations. We dread high mountains and long mileages, but when we resign ourselves and start them, suddenly we’re there. It’s brain pain not muscle pain. We need to stop thinking we can’t do it and step it up.

The view expanded fast, as if someone opened the curtains further with every few feet we climbed. The sand dune-like parched grass and cacti hills swept over the valley below us, now yellow, now grey, now purplish, under the Santa Catalinas’ towering, stony gaze.

The view and the climb gave us an excuse for a banana break on a big boulder, because there’s a limit as to how far and how high even I am willing to carry bananas and, let’s face it, Glenn has never turned down any excuse no matter how slight to take off his backpack. From there, we headed on up, up and up some more.

A camp area and a glint of a sign nailed to a tree in the forest to the far right of the trail hinted that we might have reached Saguaro National Park East’s boundary, but the official entrance came another climb later, with a gleaming silver-coloured metal Arizona Trail sign – at least the third version of the sign we’d seen so far and by far the smartest.

Mica Mountain still towered to our right, the views continued to expand exponentially to our left and soon all around us, with a perfectly straight highway down, way down in the valley stretching out infinitely towards the unknown, and the climb showed no sign of ending… ever.

My heel had been hurting for a while, but not enough to stop, take off my backpack, rummage around in my sock to see what was going on and prolong our uphill struggle, so it was only when it felt like someone was branding my foot like a farmer brands a pig, that I stopped and discovered a bullet-like hole in the back of my heel where our “new but the same” boots from Tucson’s REI had made a giant blister which must have just exploded into this burning pain. A blister pad wouldn’t stay on, so after repeatedly making Glenn extract the medical kit from the remotest depths of his backpack for several failed attempts at padding it in a sensible manner, I decided I’d have to go crazy, folded thick abdominal wound pads in half, stacked them up and bound them to my foot in a frenzy of tape worthy of an Invisible Man movie. That dressing would stay dressed.

Just as we were thinking of finding a sunny perch with a view for lunch, it was as if someone had opened the fridge door and we’d stepped through it into a cold and unwelcoming pine forest room with no windows, oozing water and dampness from Italian Spring and incongruously carpeted with crackly dry orange ferns. So we kept climbing, but hunger was getting the better of us and we eventually settled for a crack in the trees serving up a glimmer of a view through the gloom, and a hurried sandwich sitting on the trail, racing the cold to eat our lunch before our fingers froze.

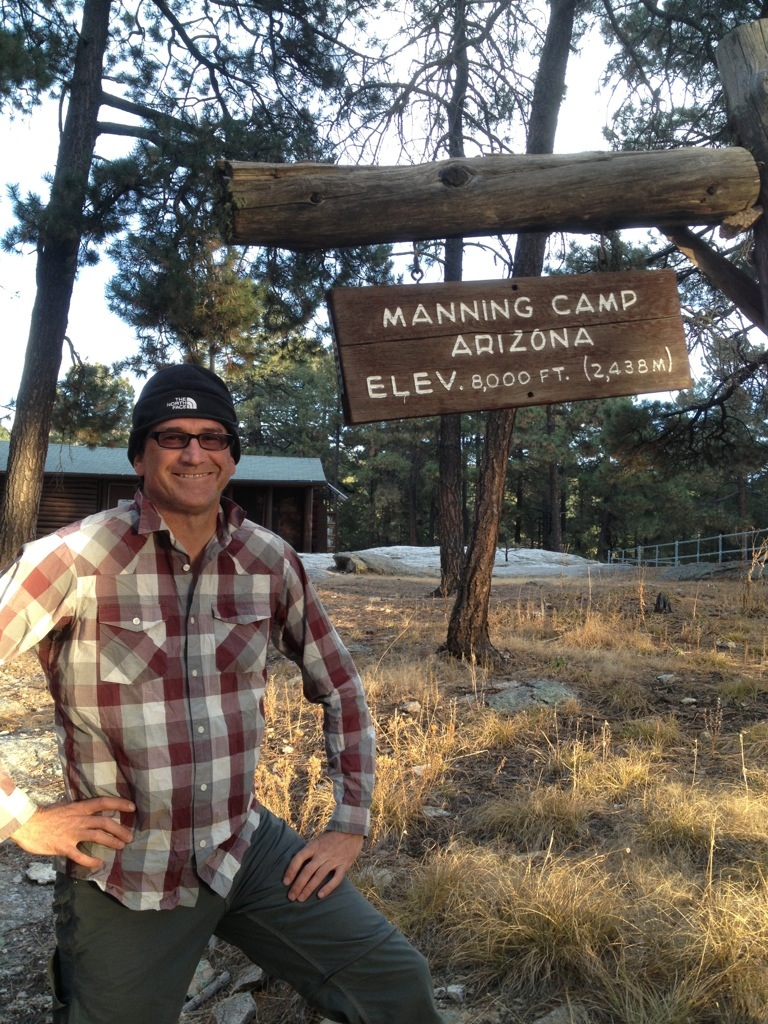

More climbing quickly warmed us up and knocked the breath out of us again as we neared 8600 ft (2621 m) and the oxygen count dropped but, finally, we reached the highest point and started the gentle, relaxing, descent on springy pine needles towards Manning Camp at 8000 ft (2438 m), ecstatic to be using a whole different leg muscle group.

Manning Camp, boasting an impressive log cabin, was built in 1905 by Levi Manning, Surveyor General of the Arizona Territory and Mayor of Tucson. Levi and his family spent several summers here raising vegetables and cattle, and escaping the heat of Tucson. He abandoned the cabin in 1907 when the Rincon Mountains were added to the Coronado National Forest. When we reached it, though, not only was Manning Camp unmanned, but someone had decided to turn the outdoor faucet off -curses!- and lock the on/ off lever in a little metal cabinet which other desperate hikers before us had already unsuccessfully tried to pry open -curses, curses, curses!- (maybe in case it froze), leaving us with the options of either risking extreme thirst or ignoring the Keep Out sign on the outdoor water reservoir gate… …And that’s all I have to say about that…

With the campfire reduced to embers, we realised just how cold it was up there at 8000 ft in December, but felt lucky that the snow in the north hadn’t caught up with us. Time to climb into our 2-person sleeping bag which normally boils us like a bag of rice, but kept us al dente that night.

We had another 12.8 miles (20.6 km) to go to reach the Saguaro National Park boundary line and 10 miles (16 km) after that to La Posta Quemada Ranch, where we were looking forward to one of the juicy hamburgers the Arizona Trail literature assured us they served up, as well as hopefully a ride to somewhere with a hot shower and a soft bed, so we hit the trail eagerly, descending through pine forest, out along a sandy, rocky stretch of trail where we could look back and see the monster of a mountain we’d been up and were now coming down, and on into grassland sprinkled with the occasional aloe and cactus, home to Grass Shack camp.

Despite the long downhill, we were still burning up calories like a fire devours kindling, so we made the most of a restaurant-sized slab of water-smoothed rock rolling over a cliff where the neon entrance sign and waitress with menus should have been, unpacked the food bag under an overcast sky and laid both ourselves and the usual salami sandwich prep paraphernalia out; wet wipes to wipe at least the more obvious dirt off our hands, the lighter to disinfect the penknife blade, the penknife waiting to be scalded into submission, a pile of bread and Mexican tortillas somehow much larger than the number of meals we’d have before we could resupply despite careful counting when we packed them, olive oil spray, salami, tasty little red organic onions, pigeon egg tomatoes and sweet, life-restoring black Arizona dates; the perfect feast… if we hadn’t been eating the same thing twice a day seemingly forever.

A siesta would have been nice, but we needed to make it out of the park and on to Vail to re-supply, so we re-packed, heaved on our backpacks and launched ourselves back down the trail, now passing cute little rainbow hedgehog cacti cuddling into other vegetation, ringed with green, yellow and striking pink and, soon after, fishhook cacti, which grew gradually from cannonball sized to almost my size, …but we were beginning to get very disappointed at the lack of saguaros in Saguaro National Park. I’d waited years and fretted over several failed attempts to visit the park to see the saguaros over the past five years and now we were here, we’d walked 10 miles (16 km) since we entered the park and we hadn’t been able to admire a single one.

…And then they were everywhere. With just 7 miles (11 km) to go to the boundary, the saguaros soared up all around us, pushing owl nests up into the sky, defying gravity with lead-heavy, water-filled limbs reaching out at impossible angles, some dead and exposing their wooden rib cages, others proud and surveying the view of the desert, the Huachuca mountains and Mexico.

We passed Hope Camp (a desolate place with no water and no camping allowed) and, just past the park boundary line sat down in an unexpected patch of shade to eat yet more salami sandwiches. While Glenn took a nap I should have been sharing, I counted six distinct kinds of cacti in just over 100 square ft (10 sqm); a randomly selected and highly representative patch. The saguaros were in the extravagant company of red cholla “trees”, yellow cholla “trees”, fishhook cacti too wide for me to get my arms around (admittedly a pretty stupid idea in the first place – see photo), various varieties of hedgehog cacti and prickly pears; a wonderland of brightly-coloured, crazily shaped plant life which could have been straight out of a made-up planet in a science fiction movie.

Our descent off Mica Mountain now ended, a rolling cacti desert-scape bumped off towards the horizon. The temperature was in the high 80s F (30s C), we’d left many miles in our wake and our energy levels were waning, but the thought of hamburgers, a shower and a bed kept us walking.

We hadn’t seen another soul since the chatterbox who left us on Reddington Road several days earlier, but our aloneness ended as quickly as it had begun, this time courtesy of a friendly mountain biker who Glenn reckoned looked spookily like Republican running mate Paul Ryan; a nice guy who would later accidentally almost run Glenn over on a trail bend on his homeward lap, maybe in subconscious revenge for Glenn going against the Texan tide and voting Democrat.

By now, I felt like I was dragging myself through the desert on my hands and knees and so did Glenn. After taking an age to round a bright red cholla tree, it suddenly dawned on us that we were still drinking the weak electrolyte mix we’d concocted for earlier, cooler places and that it was no match for all this sweating in the desert. Sure enough, a doubling of the dose perked us up like a giant cigarette would hyper-charge a smoker.

We were in the zone now, going up and down those dune-like hills, speeding between the cacti as if the hamburgers were giant magnets and we were made of iron.

Some time later, we powered into La Selvilla picnic area and topped up with an extra two litres of just-in-case water while we chatted to someone called David who seemed to be going through a very tough time in life. When we found him, he was sifting through a pile of brand new, shiny and way too heavy equipment, trying to figure out how he was ever going to carry it up a mountainside, just as we had done a few months earlier. We felt his pain… OK and slightly smug that we’d never do that again. (Famous last words…)

A downhill, an uphill and a roundabout bit in redder earth later, we saw what could only be La Posta Quemada Ranch on the other side of a deep dry riverbed from the climbing trail where we stood. The sun had set and we had only 30 minutes of grey light to reach sizzling, oh so tasty hamburgers before dark. We could see horses and people and called out to ask the way, but despite repeated attempts, they couldn’t or wouldn’t hear us, so we hiked half a mile back the way we’d come and turned left and then right following some hoof prints, finding ourselves still a thorny thicket away from the ranch’s boundary fence. More scrambling and scratched arms later, we stumbled back down into the riverbed, then up the bank further down, emerging into the back of the ranch. There was no hardship we weren’t prepared to go through to get those hamburgers. Surprised horses watched us walk past and some dogs half-heartedly barked at us. Eventually, a suspicious-looking lady in her fifties soon joined by a similarly-aged suspicious-looking man who must have spent a good amount of time that morning tying a very fancy handkerchief knot in the one around his neck, which somehow seemed to mesmerise me as I tried to figure out how he did it, came out to ask us what we wanted. Well our need was simple: Two hamburgers, please!!! Lady: “We closed at 17.00h.” (It was 17.20h.) Us: “We’ve walked several days to get here. Do you have any food at all you could sell us?” Man with fancy knot in his kerchief: “No. You’ll have to go to Vail.” Well, four miles walk isn’t very far with a hamburger caressing the inside of your stomach, but it is when it’s going dark, disappointment and craving for steaming hot red meat are searing a hole through your brain and your feet feel like they’ve been chewed on by a lion.

We walked and walked and walked in the moonlight and our headtorch light on a road which, for the most part, ended only at that ranch, so the chances of a lift were nil, with the wadge of padding on my heel painfully pushing my toes into the end of my shoes, stubbing them with every anguished step and, as I discovered later, turning two toenails a deep and stormy lavender colour Provence would be proud of. Then we joined the main road into town and hobbled our way through broken glass and water drainage ditches, aiming for a Walgreen’s pharmacy we could see in the distance. Now the whole of my bad foot was puffing up like a cobra and the other one swelling in sympathy. Glenn led the final trudge down the tarmac edge and into Walgreen’s parking lot.

Now, Walgreen’s, the super-store pharmacy with fluourescent strip lighting and shelving packed with chemicals we all pretend are good for us, is not somewhere you’d usually be any more pleased to be than under a bridge at night in a bad New York neighbourhood with a broken down car, but we were just ecstatic to bath in its bright lights, soak in the glow of the eye-popping buy-me packaging and chat to friendly humans with large name tags. Well… that was until they told us there was no hotel in Vail, at least… Could Vail be the only town in the US with no hamburgers and not even one lousy bed for rent???

It’s lucky we’re not completely stony broke (yet), otherwise we would have had to spend the night camping huddled next to one of the sickly bushes surrounding the over-sized car park, wondering what might be edible in Walgreen’s that doesn’t give you an unnatural green glow. Instead, we phoned the taxi company we’d used in Tucson and, after thirty minutes limping aimlessly around Walgreen’s clinical aisles in our very unhygienic rags, much to the amusement and curiosity of the staff and occasional customer, Ricky appeared at the door, his taxi steaming in the cold, and drove us 45 minutes, all the way back to the very Ramada Inn on Tanque Verde Road we’d left a few days before. A complete anti-climax. Ah yes, and the box we’d posted ahead of ourselves with our treats and a few essentials was now stranded at Vail’s post office.

As we coaxed our battered selves into the shower that night, we wondered at how things can so easily turn out so differently from what you expect…

Love the pics!