We propelled ourselves 20 miles back towards Flagstaff and 50,000 years into the past to visit Meteor Crater which, yes, is just a big hole in the ground, made by a fairly small meteorite which hit the earth at between 24,000 and 40,000 miles an hour, depending on which of the museum signs you choose to believe. Useless fact of the day: 1 ton of meteorites fall to earth every day.

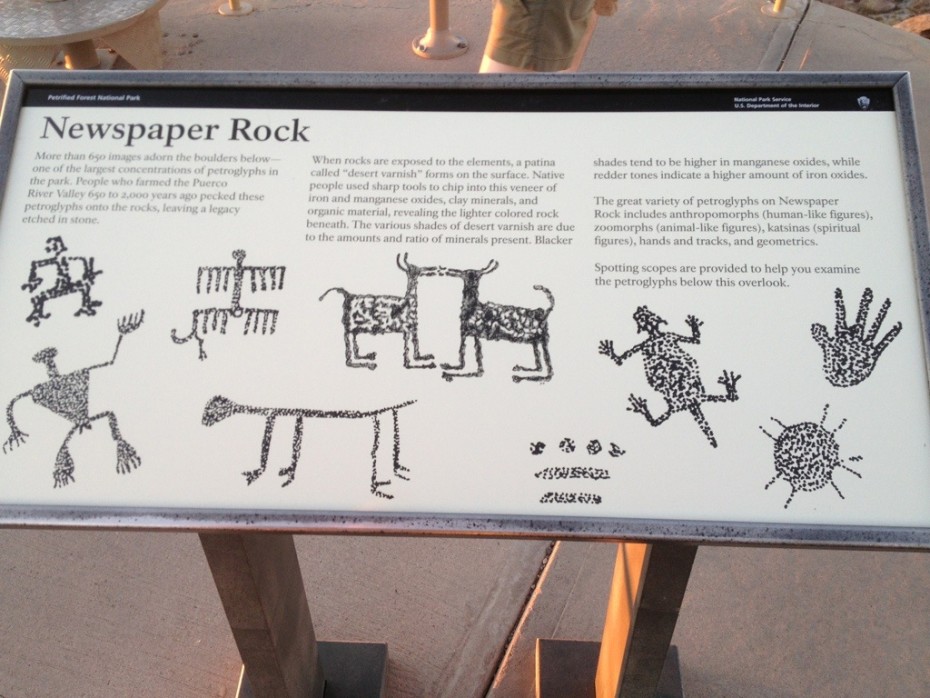

After a night in Holbrook’s iconic Route 66 concrete wigwams and my taking a truckload of classic car photos, we headed East to take endless photos, this time of dead wood. Well, it was 225 million-year-old petrified wood studded with a kaleidoscope of semi-precious crystals and minerals of every colour under the sun; from purple to bright yellow, over to green and round to plain wood-colour, so we’re not quite as crazy as we might seem (not quite). Useless fact of the day: 1 ton of petrified wood is stolen from this national park every month…, which explains why there are countless roadside stores selling petrified wood ranging from a stick for 5 USD to a large but thin sliver of amethyst-coloured beauty for 5000 USD. Apart from staring at dead wood, Newspaper Rock told us indecipherable stories in beautiful petroglyphs and a few mini hikes took us through “painted desert” scenery of hills made of blue and purple, and red and yellow layers of sand icing.

We almost missed the early 1900s movie set style wooden Hubble Trading Post, as we’d forgotten to switch our clocks to Navajo Nation time, which is an hour ahead of Arizona time and presumably serves to keep the multi-state reservation on a single time zone. They had a collection of the finest Navajo and Hopi artwork for sale, but the eye-watering prices had us running for the pickup in no time at all.

Canyon de Chelly (pronounced “Che”, as in Guevara, which is apparently closer to the original Navajo name, so as Glenn said, why don’t they just change the spelling? It would save the tourist office untold explanations and frustration) was our next stop and produced probably the second worst meal of my life, after the Brown Café (see Winslow adventure in previous post).

We stayed at the promisingly named Thunderbird Lodge, just inside the park, having arrived starving and late and in the middle of nowhere, so the lodge’s canteen, popular with the Navajo clientele, seemed like the only way to go. It must be pretty hard to make beef chunks on rice taste like dead rat on old mattress, but they did a great job and charged us 40 USD for the experience. Some lost-looking Italians, smarter and better fed than us, took one look and disappeared into the safety of the Navajo food-free outdoors. I have a theory, which is that the Navajo made great warriors because they were were able to keep themselves in a constant state of anger by thinking about the terrible food awaiting them at home after a hard day’s cowboy-hunting…

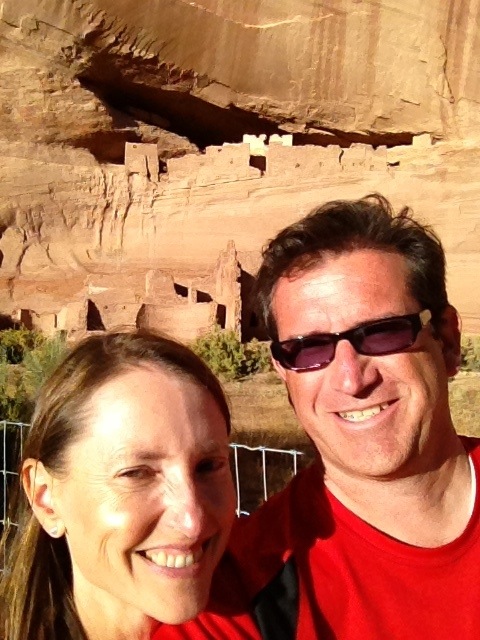

The Canyon de Chelly itself is, as with most Navajo tourist attractions, both beautiful and bound by enough access restriction rules to make Alaskan oil drilling plants seem like welcoming places. There was only one place inside the canyon which we were allowed to visit without a wallet-scalping guide, which was the White House: Glenn’s shin splints braved the 3 mile and very steep round trip hike to admire the spectacular cliff dwellings of what are much more likely to be Hopi than Navajo ancestors. The rim views of the Canyon were also well worth the drive and it was great to see that a lucky few were able to continue a relatively untarnished, natural way of life within the canyon’s walls. Disappointingly, we didn’t get to see the pictographs of the ominous arrival of the Spanish conquistadores in the early 1500s, but a postcard filled us in.

Longing for good food and espressos, we headed from the Navajo Nation to the Hopi Mesas. The Hopi being a tribe of more sedentary farming ancestry, know the significance of good cooking and hold it in high regard. Their ceremonial, corn piki bread -thinner than wafer-thin and surreally purpley-blue- is a testament to this fact.

The three Mesa (plateau) villages are cunningly camouflaged as an extra few metres of rock face, built to house Hopi plains villagers worried about reprisals from the Spaniards for the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. Each Mesa specialises in a craft; from silversmithing to pottery and it’s clear that many Hopi (and Navajo) are exceptionally gifted artists.

It takes a while to see through the ramshackle state of the Hopi villages and evident poverty which you’re not allowed to photograph, but once you’re tuned in, you start to appreciate the elegance of the round wooden beam ceilings lined with branches (they could almost be Spanish) and the multi-storey adobe walls supporting flat roofs with the beams peeking out at the top. Now I know where the Sedona town planners drew their inspiration from.

Unfortunately, the Mesa villages are increasingly falling into disrepair, they don’t house espresso machines, and they’re used mainly for ceremonial purposes centred around the underground kiva ritual rooms. Third Mesa’s Old Oraibi village dating from 900 AD (or the years 1100 or 100 AD, depending on whose account you believe) had few buildings still standing, making for a lightening tour with our 10 year-old guide. An off-limits ruin of a Spanish Catholic church was still visible, though probably provided little comfort for the Spaniards’ introduction of smallpox at one point reducing the Hopi population to just 800.